The Advocates of Notre-Dame and the Advent of Cultural Heritage

By Cierra Santay

We take for granted today that Notre-Dame cathedral is something that should be cherished and preserved. This has become obvious in the wake of the 2019 fire - of course millions of dollars are going to be spent repairing and restoring the building! We understand the cathedral today through the lens of “cultural heritage,” as one of the tangible and intangible things that are being passed down through the generations and so need to be preserved for the future. But this was not always the case. The concept of cultural heritage had to be invented and the cathedral played an important role in that process.

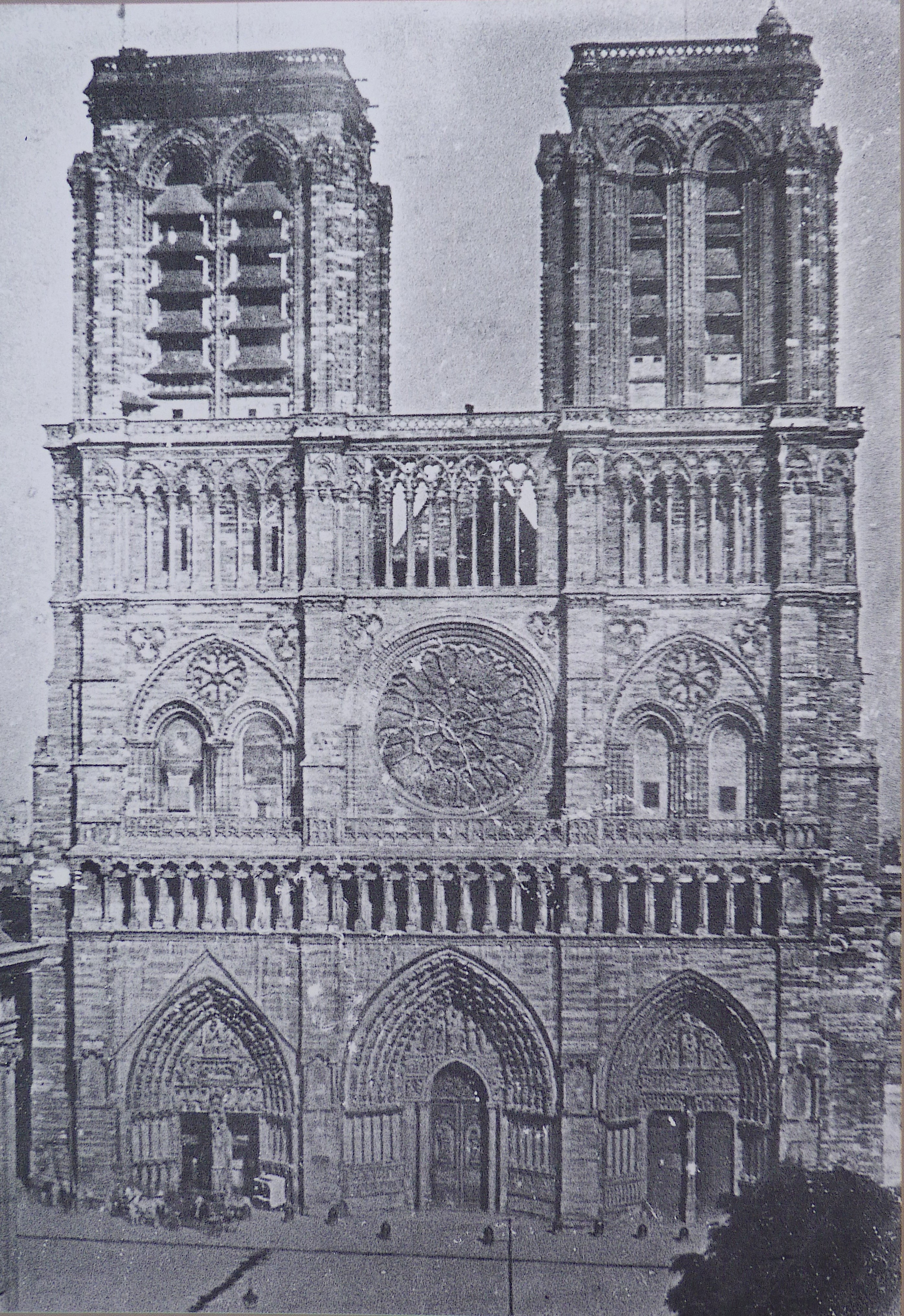

|

| Daguerreotype Vincent Chevalier, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Cultural heritage was an invention of the Enlightenment, a philosophical revolution that took place in the 18th century and set the foundations for modern society. Many ideas that are commonplace today are products of the Enlightenment, including reason, liberty, constitutional governments, and the widespread advent of the separation of church and state. France was an epicenter for the Enlightenment, where it overlapped with the Revolution. In the middle of all the philosophical and political upheaval, a few people in France started loudly stating their disapproval for the treatment of what they considered to be their national heritage.

In 1790 a man named Puthod de Maison-Rouge was one of the first voices that spoke out against the destruction or privatization of items from previous regimes. His outrage stemmed from the government’s plan to sell items confiscated from the clergy and nobility during the Revolution to private collectors. He raised a petition against the sale and fervently argued that selling the items to private collectors would deprive the French people of familial heritage that he argued would evolve to a symbol of national heritage. The government heard his outrage and created general legislation as a result. But the legislation did not make the impact Puthod had hoped because the French government was still preoccupied in its post-revolutionary state.

The next voice that made a significant difference was that of Abbe Gregorie. In the 1790’s he was deeply involved in the French government. He championed a variety of different ideas from the abolition of slavery to education and agriculture. But his set of reports on cultural heritage to the French Convention in 1794 set off a chain reaction that still lives on today. His main argument was that “national objects which, belonging to no one, belong to all.” His most impactful contribution to this issue was the creation of the noun "vandalism." The root “vandal” is a historical reference to the Vandals and other “barbarians” who occupied western Europe at the of the Roman Empire and had a reputation as destroyers of art. Gregorie used the word for the destruction of art that took place during the Revolution to label it as destruction carried out by ignorant, uncivilized, and violent people. The report in which he used the word was re-printed thousands of times and was disseminated all throughout Europe. The effect of this one little word was profound. If the political environment created by the Enlightenment was already a wildfire taking down monarchies and establishing reason as the true king, then this little word was more fuel for the blaze. It identified the destruction of art as the opposite of everything the Enlightenment stood for.

|

| Victor Hugo. Portrait photograph by Etienne Carjat, 1876. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Now we come to one of the loudest voices for cultural preservation and for Notre-Dame, Victor Hugo. Hugo is best known today as the author of the Hunchback of Notre Dame, the novel that has endured over time and been adapted by the likes of Disney. But he also published essays on just how angry he was that no one cared about the monuments that were suffering collateral damage from the revolutions that had plagued France. In one essay, titled Guerrue Aux Demolisseurs or War on the Demolishers from 1832, he devolves into innumerable examples of what he considered to be “the hammer that is mutilating the face of the country.” He mentions many French monuments including Notre-Dame, the Sorbonne, and Saint-Germain-des-Pres, while referencing famous figures like Joan of Arc and Catherine De Medici. I wish there were a stronger word to describe just how outraged Hugo was that no one saw these monuments as important pieces of French heritage. He was so mad that it is genuinely funny to read the essays he published about this topic. One example: “Vandalism is celebrated, applauded, encouraged, admired, caressed, protected, consulted, subsidized, defrayed, naturalized. Vandalism undertakes work for the government. It has underhandedly inserted itself into the budget, and quietly eats away at it, like a rat at its cheese. And it certainly earns its money well. Every day it demolishes something of what little remains of this admirable old Paris.” But the true center of his seething anger was his beloved Notre-Dame.

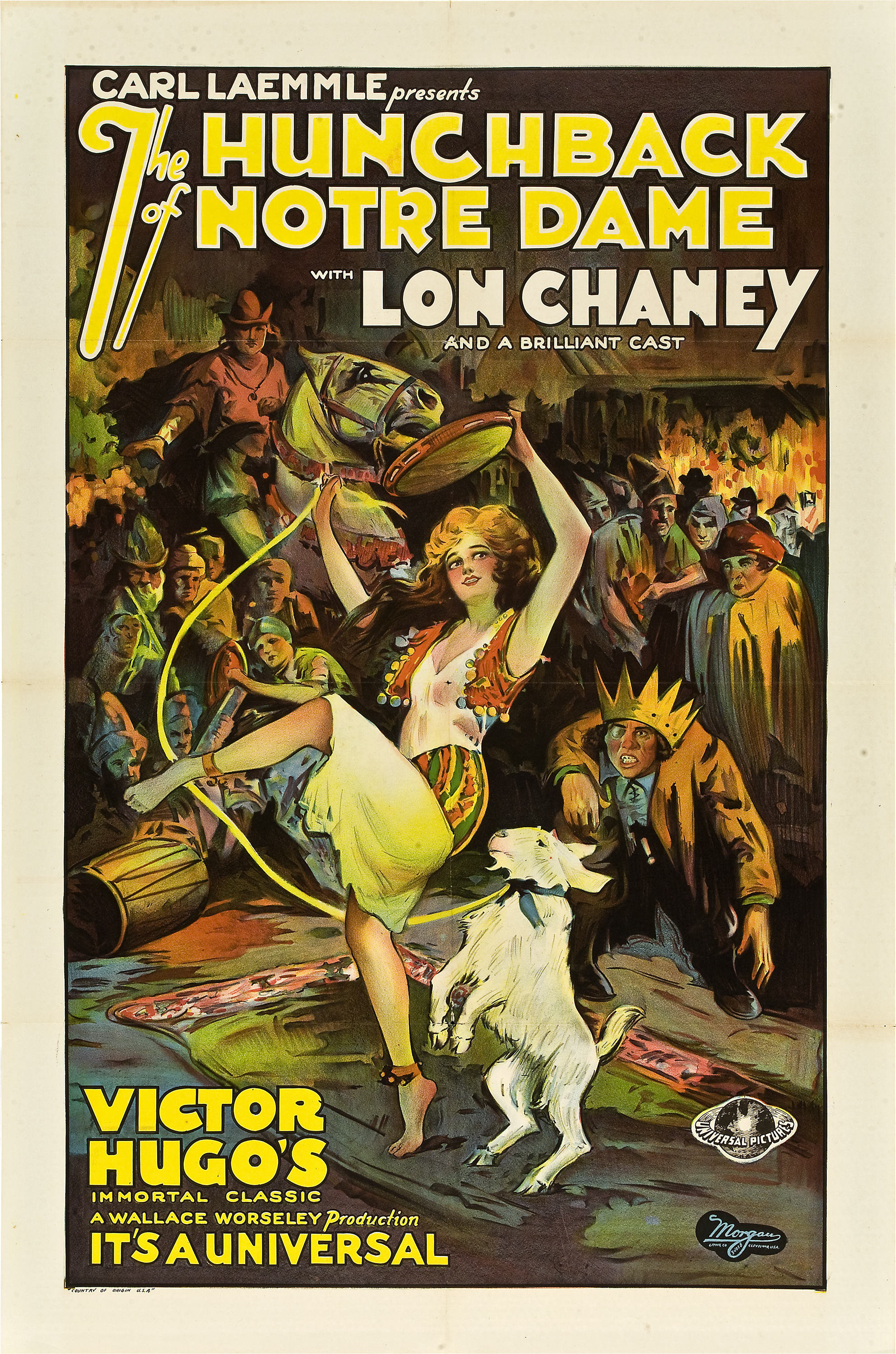

|

| Poster for the 1923 movie adaptation of the Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Universal Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The reason why Victor Hugo wrote Notre Dame de Paris aka The Hunchback of Notre Dame is simple, he loved the cathedral deeply. Hugo was at the beginning of his illustrious career as one of the most enduring French writers when he wrote the 940-page love letter to Notre Dame. First published in 1831, it is the story of a disfigured bellringer named Quasimodo and his love for the beautiful gypsy dancer Esmerelda. Their love story takes place with the cathedral serving as the backdrop and as a supporting character. Hugo dedicated two whole chapters to just describing the cathedral. He was angry at how the revolution had defiled the cathedral while the shoddy restoration attempts further defaced the monument. The damage done to Notre-Dame by the French revolutions is unquantifiable. There is no reliable source of documentation to attest to the state of the cathedral before the revolutions. We do know that revolutionaries lopped off the heads of statues and left them as rubble in front of west façade where they would eventually be used as a public urinal space.

In the end, the ideas that Puthod Maison-Rouge, Gregorie and Hugo championed echoed all throughout the world. Hugo’s book drew so much attention to the cathedral that the French government was forced to begin the process of finding an architect to restore Notre Dame. That architect, named Eugene Violet Le Duc, would create the cathedral as we know it today. As for the idea of cultural heritage, it has become a widespread common ideal. Innumerable countries around the world have countless spaces dedicated to their specific heritage and historical events. They all have the same common goal in mind, to preserve and protect their heritage for future generations. So, Puthod, Gregoire and Hugo have finally been heard.

Sources:

Victor Hugo and Lyn Thompson-Lemaire. Essay. In Oeuvres complètes De Victor Hugo, De L'Académie Française, 279–287. Paris: Vve Alexandre Houssiaux, 1864.

D. Poulot. “The Birth of Heritage: 'Le Moment Guizot'.” Oxford Art Journal 11, no. 2 (1988): 40–56.

Joseph L Sax. “Heritage Preservation as a Public Duty: The Abbe Gregoire and the Origins of an Idea.” Michigan Law Review 88, no. 5 (1990). doi:10.2307/1289119.

Astrid Swenson. The Rise of Heritage: Preserving the Past in France, Germany and England, 1789-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Comments

Post a Comment