Hatred Immortalized in Stone: Ecclesia and Synagoga at Notre-Dame Cathedral

By Danielle Cooke

There is a deep history of anti-Jewish sentiments to be explored in the European past. At times visual testaments to such feelings are revealed, as in the case with the Ecclesia and Synagoga sculptures on the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, France. When hatred is immortalized in stone, it is both hard to ignore and hard to forget.

Discrimination against Jews in western Europe in the Middle Ages was both political and religious and showed how those two parts of society were intertwined at the time. In the 11th and 12thC centuries, the Jews of England and France “belonged” to the king or to other powerful nobles. This set them apart from the rest of the population. The kings and nobles protected “their” Jews, but there was no one who could protect the Jews from lords who wanted to raise taxes from them or borrow money from them. This allowed the kings to use the Jews as a buffer between themselves and their people, since they didn’t have to tax the general population to meet their needs. But at the same time, it made the Jews a target when the people were unhappy with a king and his rule. Towns with new self-governing structures were determined to throw the Jews out of their communities. The feelings of the kingdom’s subjects were clear, and the rulers soon followed their wishes. Philip IV first ordered Jews to pay for their own mandatory identification badges and subjected them to higher taxes. But as the country developed, the role of the Jews as a source of tax monies became irrelevant and outdated. With their only political advantage drained away, in 1306 Philip IV drew a line and expelled the Jews from his kingdom to appease his subjects and display his power.

Meanwhile, the church used the symbolic figures of Ecclesia and Synagoga or Church and Synagogue, to represent it’s understanding of the relationship between Christianity and Judaism, Christians and Jews. The Exposito Cantica Canticorum, a 12th century song by Honorious Augustodunesis, tells their story. Synagoga is the mother of prophets and patriarchs, but she is guilty of deviation from the law and the murder of Christ. Ecclesia is the vindissima virga , the new bride of the lamb and the mother of believers. In the end, according to the text, Synagoga will rejoin the true bride Ecclesia to unite with Christ, the bridegroom and judge. A bit cryptic, is it not? The most important idea that is that in the eyes of Christians, Synagoga is meant to turn back to Ecclesia and then will be forgiven by God. In the real world, that means followers of Judaism are promised redemption if they turn back to the rightful church by converting to Christianity. The imagery we will soon see at Notre-Dame illustrates a tension that exists between harping on guilt and advertising this promise of redemption.

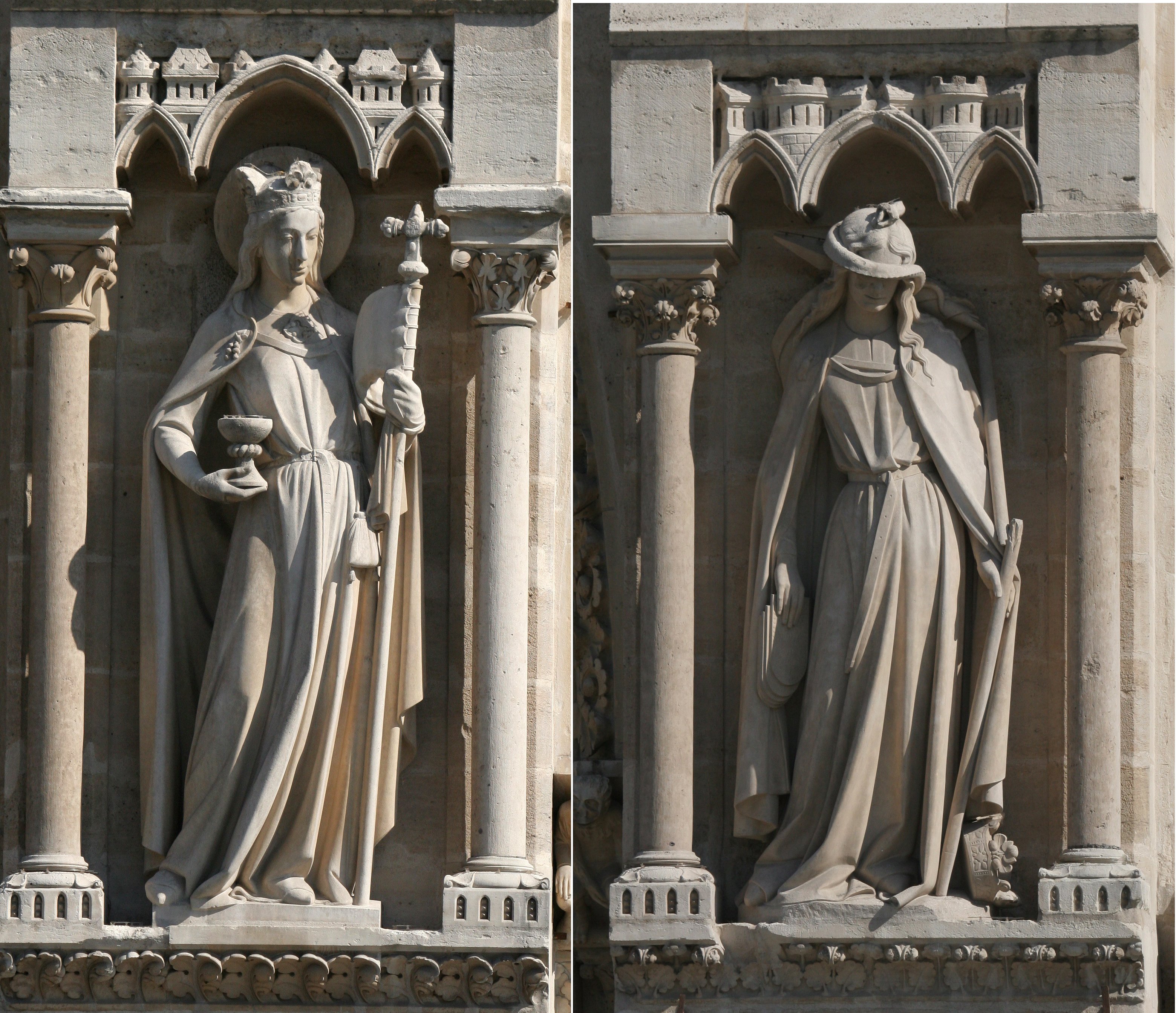

This relationship between Ecclesia and Synagoga is represented in the sculptures that appear on the western façade of Notre-Dame. Their representation on the church was just one of its innovative features when it was first built in the 12th and 13th centuries. While the sculptures currently on the cathedral date from its 19thC restoration, they are very close to the medieval originals. Gothic cathedrals at Strasbourg and Bamberg also employed this kind of imagery.

| |

| Detail of Ecclesia. Julie Kertesz from Paris neighbourhood, France, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Looking more closely at the sculptures on the cathedral in Paris. On the right, we see Ecclesia in all her glory, her head backed by a circular halo denoting her holiness and virtue. In her right hand she cradles a chalice, likely representative of holy communion. In her left hand she holds an intact staff with a banner, topped with an intricate finial in the shape of a cross. A crown rests solidly atop her head, and around her waist a pouch denotes wealth. On the left, Synagoga is blinded by a fang bearing serpent that wraps around her head menacingly. She carries her tablets low rather than lifting them up with pride. Her staffis broken in two places, and her crown has tumbled to the ground and lays beside her feet, tipped onto its side. Her face is cast downwards, turned away from Ecclesia, symbolizing her separation from the faith and her reluctance to return. She is a pitiful sight, especially when juxtaposed with the majesty of her counterpart.

|

| Detail of Synagoga. Vassil, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The images of Ecclesia and Synagoga sent a very public message about the church’s stance on Judaism. Their distressing image of Synagoga is an attempt to emphasize the guilt that their creators thought should be felt by those following the wayward path of Judaism. Surely a Jewish resident of the city would have felt – and would still feel - uncomfortable when stumbling upon these figures on their morning walk. Would you feel welcomed into the arms of redemption and forgiveness after seeing this portrayal of your faith? I surely wouldn’t. And so centuries of Jewish struggles are immortalized in stone on the majestic west facade of the Notre-Dame Cathedral.

Sources:

Comments

Post a Comment