Drama from the Dead at Notre-Dame

By Caitlen Cameron and Marian Bleeke

From watching one of the hundreds of royal themed shows on Netflix or Hulu, you know that there is drama hidden behind the castle walls. Most of us would believe that the drama was made up by Hollywood to draw us in and give some binge-watching necessity to their shows. But did you know that some of that drama is true? And there was even some of that juicy drama back in medieval times? Welcome to The Crown meets Notre-Dame circa the 1100s.

| Tomb of Bishop Simon Mattifas de Buci. Zmorgan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Digging into histories of the people buried at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris reveals one story worthy of Game of Thrones. Most of the men buried at the cathedral in the Middle Ages were bishops and canons who devoted their lives to the church and were able to donate enough money to get a nice spot in the rose window spotlight. The exception to that rule is Phillip, the youngest brother of King Louis VII, who was buried in cathedral in 1161 when he died at the age of 29 after a short but dramatic life.

|

| Louis VII of France from the

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève,Ms. 782 Via Wikimedia Commons |

As the second son of Louis VI, Louis VII was originally meant to have a career in the church and was educated at the cathedral school at Notre-Dame. But when his eldest brother Philip suddenly died from falling off his horse in 1131, Louis life quickly turned around and he was unexpectedly given the throne. In 1132, as Louis was getting ready to be crowned, his mother was about to have her eighth child and last son, Philip. Since the first son died, you might as well give the same name a second try a year later, right?

Louis and the younger Phillip’s relationship was a classic sibling rivalry with the oldest child fighting with the youngest. Since Philip had no chance of gaining the throne himself, he pushed his way into the church to gain his power and prestige. In 1147, another one of their brothers, Henry, resigned his powerful positions in the church to become a Cistercian monk. The determined Phillip took over his positions and became the abbot of the collegiate churches of Notre-Dame of Etampes, Corbeil, Mantes, Poissy and Saint Melon of Pontoise. And since Philip still had more to prove to his brothers, that same year he also became the treasurer of Saint-Corneille of Compiegne.

This last position led to drama between Phillip and Louis VII. In 1149, the king and the Pope had agreed to transfer administration of the church Saint-Corneille to the monks of Saint-Denis. But Philip was resistant. He didn’t want to lose control over the relics kept at Saint-Corneille. As a result, when the monks arrived to take over, he and a group of armed canons and laymen shut themselves up in the church and took possession of its treasury and its most precious relics. You could compare this to having a little kid locking himself in his room so he wouldn’t have to go to school.

Louis VII and Henry, who had left his monastery to become bishop of Beauvais, traveled to Saint-Corneille to try and make an agreement with Philip about the transfer, but he still wouldn’t surrender. Upon seeing the royals arrive in the town, the local townsmen realized how foolishly Philip was acting and scared all his followers out of the building, threatening to punish anyone that was helping his cause. Philip was now alone in his fight. The townspeople left him unharmed due to his royal blood and pity for his desperate fight. While the monks eventually took over the building, Phillip did not give the treasury up for years.

Since this power-play had such so much success for Philip, he tried another a few years later. This time he took on the canons of Notre-Dame of Mantes and lost. Philip claimed that he could summon the canons at his will anywhere he pleased because he was their abbot. He wanted the canons to travel 30 miles east to Paris by cart, just to have their usual meeting. He may have thought that he would have more control over the canons if a few of them met in Paris instead of all of them gathering in Mantes. The canons disagreed and Louis VII ended up having to get involved another dispute caused by Philip’s stubbornness. This time Philip didn’t get his way. Louis ended up siding with the canons in a decision from 1152.

|

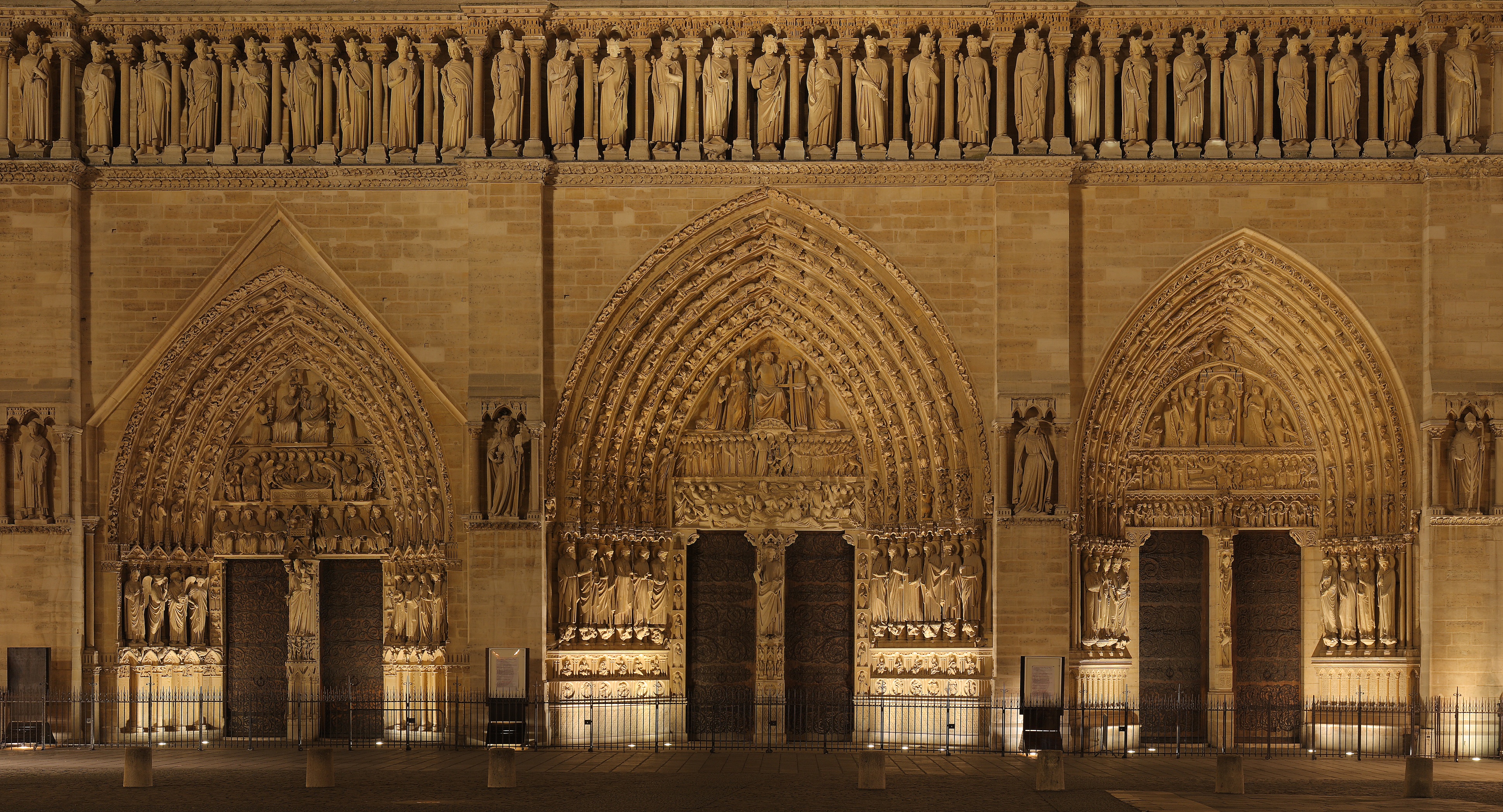

| West facade of Notre-Dame at night. Benh LIEU SONG, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Philip’s last chance at a position of real power came in 1159 when he was almost elected Bishop of Paris. He already had a long relationship with the Notre-Dame as a student, a canon, and then a deacon of the church. According to a contemporary source, Robert of Torigny, he was offered the position of bishop but turned it. Given all he had done to gain power and prestige, it sounds unbelievable that he would pass this one up! But if you think about his age and circumstances at the time, his decision sort of makes sense. Philip was only 27 in 1159, the church career he had devoted his life to was failing him, and his family was moving on without him. To try to improve his reputation he started to make substantial donations to churches around Paris, including to building the new cathedral church for Notre-Dame that was just being started. It was while he was trying to repair his image that Philip died in 1161.

Philip was one of the very first people buried in the new Notre Dame where construction had only just started. He was followed by a few other members of the royal family. Queen Isabella of Hainault was buried there in 1190. And another Philip, the first son of Louis VIII, was buried there in 1218 when he died at only 9 years old. This Philip is most important in that his death made way for his younger brother, Louis IX or St. Louis to be the next king. Neither of them could compare to Philip in the drama they caused during their lives.

Sources:

Andrew Lewis,. “The career of Philip the Cleric, Younger brother of Louis VII.” Traditio. Vol. 50 (1996): 111-127.

Mapping Gothic France. “Louis VII.” Accessed March 18, 2021. http://mappinggothic.org/person/378

Comments

Post a Comment